Australian Megafauna

The word 'megafauna' means big (mega) animals (fauna). In the context that we are using the term, it means Australian animals that collectively died out in a mass extinction about 46,000 years ago. They were very large, usually over 40kg in weight, generally at least 30% larger than any of their extant (still living) relatives. Although many of them were marsupials; including giant kangaroos and wombats as well as other strange beasts like the marsupial lion, there were also huge snakes, lizards and birds in ancient Australia.

These animals had existed here for around 11 million years, then within just a few thousand years, most of these giant animals disappeared. There are several theories to explain this relatively sudden extinction and the discoveries at Mammoth Cave have helped with explaining their disappearance.

Thylacoleo carnifex - extinct marsupial lion

(Thylacoleo) pouch lion (carnifex) flesh eater

(Thylacoleo) pouch lion (carnifex) flesh eater

Thylacoleo was the largest carnivorous (meat eating) marsupial to have ever lived on earth.

It had the most unique tooth pattern of any known animal, with enormous slicing premolars (4 – 6 cm long shearing blades on each jaw that slid against each other like a pair of scissors) and large stabbing incisors, it had what was possibly the most powerful bite of any mammal, living or extinct. With its powerful jaws and massive forelimbs with huge retractable thumb claws for grasping and holding down its prey, it probably hunted other large animals such as Zygomaturus and Simosthenurus.

It is believed Thylacoleo captured its prey by ambush, possibly dropping onto it from above and, like modern lions and leopards, clamping the prey’s neck and windpipe in its jaws, killing by suffocation. Opposable first toes would have provided grip and balance for climbing trees and Thylacoleo likely dragged its large prey carcass up a tree to feed, much in the manner of a modern leopard. This removed it from the reach of scavengers like the Tasmanian devil.

Although Thylacoleo was comparable to a leopard in size, weighing approximately 80 kg to 100 kg, its closest living relatives are the plant-eating koala and wombat.

Zygomaturus trilobus - large wombat-like diprotodontid

(Zygomatic) prominent cheek arches, (trilobate) three-lobed snout

(Zygomatic) prominent cheek arches, (trilobate) three-lobed snout

This giant animal was one of the largest marsupials to have ever lived, with the only known larger species being its relative, the Diprotodon. Zygomaturus inhabited the wooded coastal regions of the country, perhaps preferring a wetter, swampy environment.

With its tusk-like incisors it could grasp whole plants, dig them out of the ground with its strong claws and feed on the stems, roots and tubers. It was as big and heavy as a bull, weighing 500 kg or more and standing about 1.5 m tall and 2.5 m long.

Zygomaturus had a massive head, with huge arching cheek bones and widely flared nasal bones which may have supported small horn like structures.

Fossils of this odd-looking herbivore have been found in the South West region with no less than 20 individuals found in the Mammoth Cave deposit.

The jawbone of a Zygomaturus can still be seen in Mammoth Cave in its original location nestled under a flowstone (crystal) ledge. This jawbone is dated at around 50,000 years old, making this individual one of the last of its kind because along with the rest of the megafauna, Zygomaturus had become extinct by 46,000 years ago.

Simosthenurus occidentalis - extinct short-faced kangaroo

(Simo) short-faced (Sthenurus) strong tail (occidentalis) from the west

(Simo) short-faced (Sthenurus) strong tail (occidentalis) from the west

The Simosthenurus or ‘short-faced’ kangaroos were among Australia’s most common Megafauna species. More than 20 different species have been discovered, with two of these species first identified from Mammoth Cave. These extinct kangaroos were about the same size as a large western grey kangaroo but were much more robust and powerful. Unlike the western grey, the short faced kangaroos were leaf-eaters. By rearing up on their hind limbs and using their strong, long arms and fingers they could reach over their head to grasp high leaves and branches and pull them down to their mouth. Their powerful jaw muscles and large cheek teeth enabled them to cut and crush vegetation.

Simosthenurus had a short neck, a koala-shaped head and a degree of stereoscopic vision (that means both eyes see the same thing, but from a slightly different angle, which allows the brain to process the scene and judge depth and distance). This was important when reaching up for vegetation or hopping through the dense undergrowth. Unlike modern kangaroos which have three toes on their hind feet, short-faced kangaroos had only a single large toe. This, together with its heavy frame and large head meant it probably moved quite slowly through its forest or woodland environment. Another unusual feature of Simosthenurus was its large nasal areas which may have been used for amplifying sound for communication. They may have been very noisy animals.

Zaglossus hacketti - extinct giant echidna

(Zaglossus) great tongue (hacketti) Sir John Winthrop Hackett – past president of the board of trustees of the Western Australian Museum.

(Zaglossus) great tongue (hacketti) Sir John Winthrop Hackett – past president of the board of trustees of the Western Australian Museum.

Zaglossus hacketti was unknown to science until it was first identified from the Mammoth Cave fossil deposit in 1909. This giant extinct echidna weighed about 30 kg and stood around one metre tall (about the size of a sheep) making it the largest monotreme (egg laying mammal) to have ever lived.

Just like today’s echidnas, Zaglossus were covered in spines for protection. Zaglossus had very long back legs enabling the animal to stand, freeing its arms so that it could use its very long claws for digging out termite nests. It had a much longer, downward curving snout than the common echidna and it possibly also ate grubs, beetles, worms and other invertebrates.

Zaglossus’s sticky tongue would have been about 54cm long – the average human tongue is approximately 7cm. A sheep-sized echidna with a ½ meter long tongue would have been an impressive sight.

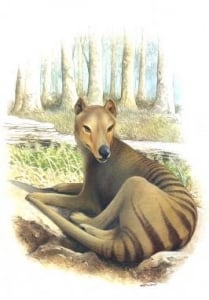

Thylacinus cynocephalus - Tasmanian Tiger

(Thylacinus) pouched dog (cynocephalus) dog headed

(Thylacinus) pouched dog (cynocephalus) dog headed

The thylacine was Australia’s largest marsupial carnivore at the time of European settlement and it was by that time found only on the island of Tasmania. It was even then a rare species, with perhaps only around 3000 animals existing at that time.

This dog or wolf-like animal was a sandy fawn to brownish colour, with 15 to 20 dark stripes over its back and rump, earning it the name ‘Tasmanian Tiger’.

However, fossil remains of this marsupial have been found throughout Australia and even in New Guinea. Thylacines vanished from the mainland of Australia around 3300 years ago, with the introduction of the dingo approximately 4000 years ago thought to be a major contributor to their disappearance on the mainland.

The thylacine had many special features including jaws which could open to an impressive 120° (the Great White shark can only open its jaws to 90°). Its tail was not like that of a dog, but more an extension of the body like that of a kangaroo. The thylacine could use the end of its tail for additional support as it sat back on its elongated back feet, the entire long heel in contact with the ground. This made it appear much like a kangaroo, which it was in fact more closely related to than any of the canine family.

The pouch of the thylacine was rear facing, to protect the young as the animal ran through their open forest or coastal scrubland territory. The mother carried up to 4 young at a time and once they were big enough she probably left them in the lair while going off to hunt kangaroos and wallabies.

It is a tragedy that the early European settlers in Tasmania blamed thylacines for the deaths of many of their sheep stock, which led to a bounty scheme being introduced. Although many of these deaths were probably due to wild dogs, vagrants or aboriginals, the government paid 1 pound Stirling for each adult and 10 shillings for each thylacine pup brought in dead. The population was decimated within a century. The last thylacine to be shot was killed in 1930, finally in August 1936 the government declared the species to be protected. It was too late. In September that year, just 29 days after becoming ‘protected’ the last known thylacine died in a zoo in Hobart.

The thylacine survived the mass extinction of the megafauna 46,000 years ago, but tragically still lost its fight for survival due to the ignorance of humankind. It is now considered extinct.